The Long Walk is not just the latest Stephen King adaptation but only the third major film based on a novel published under his pseudonym, Richard Bachman. After decades of stalled attempts to bring the story to screen, the movie finally premieres, followed closely by Edgar Wright’s eagerly anticipated adaptation of The Running Man — another Bachman novel previously made into a 1987 film starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. These Stephen King Richard Bachman adaptations draw renewed attention to King’s darker literary side, resonating strongly in today’s sociopolitical climate.

Filmmakers often look to King’s work for projects because his name guarantees audience interest, but the Bachman novels offer something distinct: stories written early in King’s career that feel incredibly forward-looking. The Long Walk especially strikes a chord, portraying a dystopian America under authoritarian rule where a brutal contest is disguised as patriotic entertainment. With its themes of oppression and despair, the film feels especially urgent amid current societal tensions, highlighting the longevity and relevance of the Bachman persona discovered decades ago.

A Harrowing Portrayal of Youth and Control in The Long Walk

The film largely adheres to the original storyline from Bachman’s novel, although with some plot and ending changes. The protagonist Ray Garraty, played by Cooper Hoffman, is a teenage contestant in a government-run endurance contest designed to uplift the American public during an era of economic hardship. Contestants are required to maintain a steady pace of three miles per hour, and any lagging performance receives warnings; three warnings result in death by shooting, known ominously as receiving a “ticket.” The last remaining walker wins a cash prize and a single wish.

What initially appears voluntary reveals itself as a cruel system with no true escape, trapping participants in a cycle of suffering and control. Garraty and his companion McVries (portrayed by David Jonsson) come to understand that the game, despite the Major’s (Mark Hamill) sadistic encouragement, exists solely to break the individuals and distract the public, who consume the spectacle ravenously. The Long Walk exposes the dark machinery of societal manipulation, where entertainment serves as an opiate to hide the truth of exploitation.

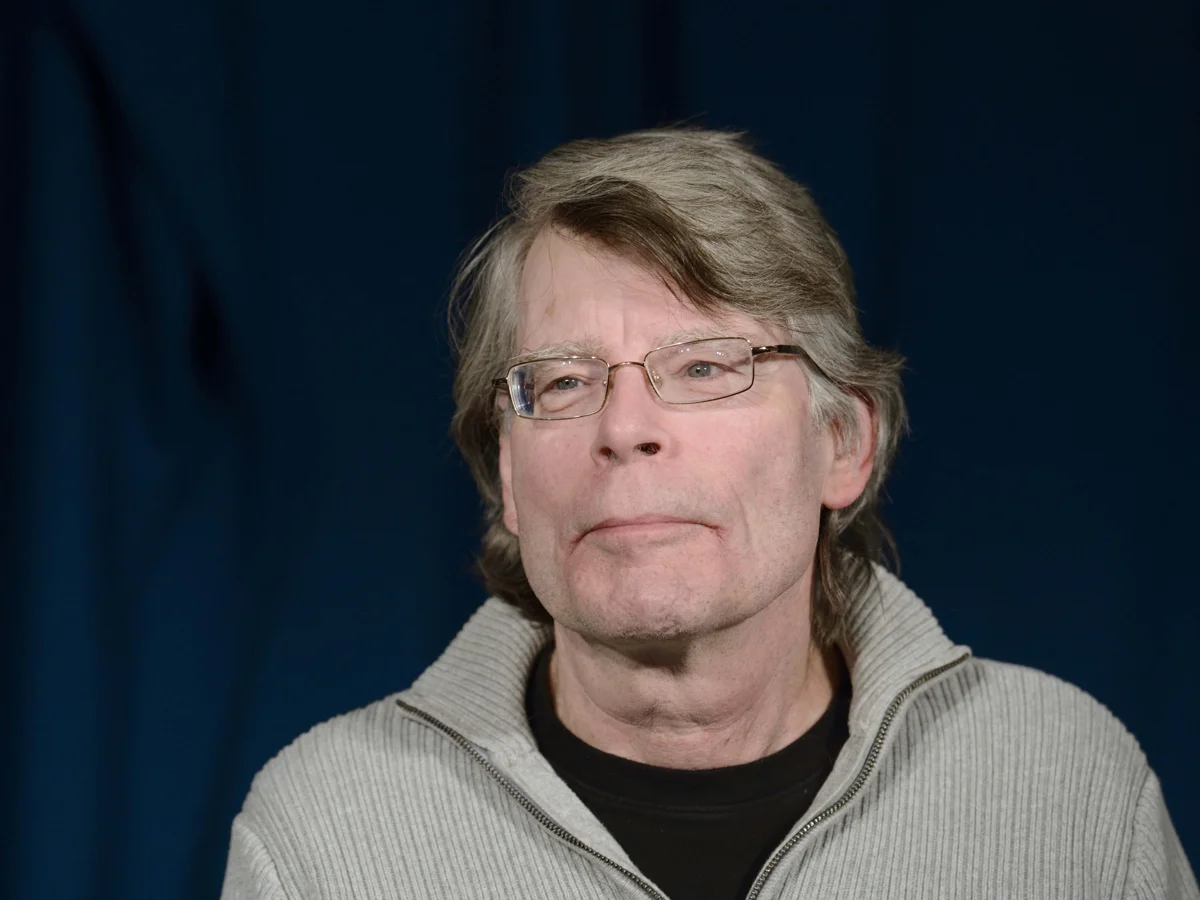

Stephen King developed his Bachman identity when his publisher limited him to releasing only one novel annually. Using this pen name, King published works that leaned more toward speculative fiction and pulp styles than his usual horror focus. The Long Walk was King’s first written novel, conceived during his time as a University of Maine student in the late 1960s but only published in 1979. It carries sharp political overtones, especially referencing the Vietnam War through its draft analogies and the Major’s propaganda that glorifies participation as patriotic. While its political allegory can sometimes feel direct, it channels the raw anger of youth facing systemic oppression.

The film, directed by Francis Lawrence, matches the book’s bleakness and relentless tone, immersing viewers in a grim narrative of endurance, friendship, and despair. Although the story was conceived nearly 60 years ago, it remains powerfully relevant, echoing contemporary anxieties about authoritarianism and societal decay.

Richard Bachman: Stephen King’s Shadowed Alter Ego

While Stephen King is often seen as a hopeful storyteller—even within his horror tales he frequently offers closure with good triumphing over evil—the stories he published as Richard Bachman embrace a bleaker worldview. The protagonists in Bachman’s books often face grim fates, ranging from death to mental collapse, and even the “happiest” outcomes, like that in The Running Man, carry a deeply somber tone unlikely to be fully captured in upcoming adaptations.

King himself has acknowledged that Bachman represents his darker impulses. He explored this duality in the novel The Dark Half, which portrays the pseudonym as a sinister alter ego coming to life, later made into a film by George Romero. In the introduction to the Bachman collection, titled The Importance of Being Bachman, King explains:

“The good folks mostly win, courage usually triumphs over fear, the family dog hardly ever contracts rabies; these are things I knew at twenty-five, and things I still know now, at the age (almost) of 25 x 2. But I know something else as well: there’s a place in most of us where rain is pretty much constant, the shadows are always long, and the woods are full of monsters. It is good to have a voice in which the terrors of such a place can be articulated and its geography partially described, without denying the sunshine and clarity that fill so much of our ordinary lives. For me, Bachman is that voice.”

—Stephen King, Author

Most audiences prefer Stephen King’s more humanist style of horror, where evil is ultimately defeated and some hope remains. This preference partly explains why films like The Mist, one of King’s darkest adaptations, received mixed responses. Viewers are more comfortable with terror balanced by redemption, such as Pennywise’s evil being overcome or Jack Torrance’s madness being confined. Yet, in difficult times, the uncompromising, grim perspective of Richard Bachman can resonate deeply as an expression of harsh realities.

The Enduring Appeal and Contemporary Relevance of Bachman’s Work

The Long Walk has long been an elusive project in Hollywood, with several directors like George Romero and Frank Darabont attempting to adapt it. The story’s allegory has repeatedly found new significance as social conditions shift. Initially a clear analogy to the Vietnam draft and war, The Long Walk now mirrors widespread fears of authoritarian government, escalating militarization in cities, declining job prospects, and a general sense of aimlessness among young men. Francis Lawrence’s unflinching approach presents a stark, unromantic view of endurance and control, rejecting the notion of this tale as simple entertainment.

In parallel, Edgar Wright’s version of The Running Man promises a return to the novel’s raw, bleak tone, moving away from the campy action of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s 1987 film. Both stories depict dystopian contests staged for a bloodthirsty public, serving as scathing critiques of capitalism and media manipulation. The Running Man’s protagonist fights to reclaim some agency within a rigged system, reflecting a recurring theme across Bachman’s work.

Other Bachman novels anticipate modern issues as well. Roadwork tells of a grieving man battling bureaucratic oppression after a family tragedy, while Rage, dealing with a school shooting, hits especially close to contemporary anxieties—so much so that King requested it no longer be printed. Through Bachman, King explores a worldview where injustice is systemic, victory is uncertain, and darkness is ever-present.

King’s storytelling varies from uplifting to terrifying, but Bachman channels a voice that suggests the odds are stacked and not all stories have hopeful endings. In this light, Bachman’s tales might be seen as mirrors reflecting the more troubling facets of the present day.

Prospects for Future Adaptations of Richard Bachman’s Novels

The Long Walk’s strong critical reception signals a promising resurgence for Bachman’s stories on screen. With Edgar Wright and Glenn Powell attached to The Running Man, anticipation is high that this adaptation will become a major event. Additionally, King’s overall adaptations continue at a robust pace, including recent projects like The Monkey, The Life of Chuck, and TV series The Institute, with IT: Welcome to Derry also set for release.

However, Bachman’s work remains a niche within King’s broader fanbase. Past attempts such as Thinner did not succeed commercially or critically, and earlier adaptations of The Running Man diluted its bitter edges with spectacle. Yet, given the current cultural mood marked by uncertainty and distrust, these darker narratives may connect more deeply with audiences willing to face harsher truths. The time might be ripe for King’s shadow self, Richard Bachman, to claim an even larger share of the spotlight in film and television.