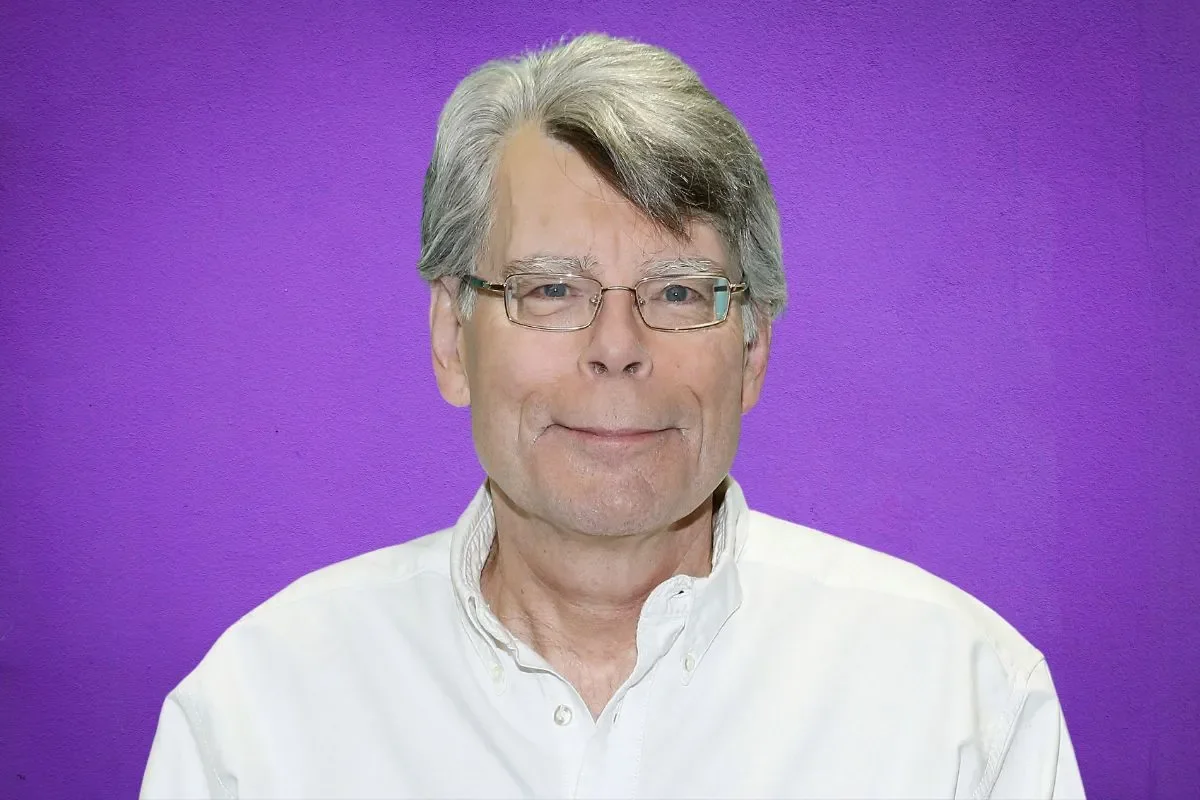

Stephen King The Running Man is a story that has sparked both praise and debate, especially following its latest film adaptation by Edgar Wright. While the movie offers an exciting and well-acted journey, comparing it to King’s original novel reveals a stark difference in complexity, tone, and impact, setting the stage for ongoing comparisons between book and film.

Comparing Stephen King’s Novel to Edgar Wright’s Film

The original novel, The Running Man, came out in 1982, authored by Stephen King under the pseudonym Richard Bachman, though he wrote it during the 1970s. Short in length but rich in content, the book delivers immersive world-building, tense drama, and thoughtful dystopian themes that stand out in a crowded genre.

King’s version of Ben Richards exists in a bleak society, pushing the character into desperate action not by choice, but by grim necessity. The book’s depiction of a crumbling world and the protagonist’s fight for survival places it firmly among King’s most powerful dystopian works, marked by sophisticated narratives and resonant metaphors.

Film adaptations of King’s stories range from cinematic triumphs like The Shawshank Redemption and Stand By Me to less memorable outings, and critics have largely positioned The Running Man as a middling effort. The latest adaptation, directed by Edgar Wright, introduces Glen Powell as Ben Richards—a modern take on the reluctant, family-driven hero archetype, echoing figures like Russell Crowe’s Gladiator and Bruce Willis’s Die Hard.

Despite its action pedigree, the movie delivers more than fleeting entertainment. From the opening moments, the film’s mood and score evoke anticipation for something above the ordinary, driven by Powell’s performance and standout music from Sly and the Family Stone. Supporting characters, including Josh Brolin’s menacing Dan Killian and Colman Domingo’s electrifying Bobby T, help elevate the material. Other notable appearances come from Michael Cera, Katy O’Brian, Martin Herlihy, and Lee Pace, each adding their own flair to the ensemble cast. This strong lineup carries the film, even when the screenplay falters.

Though Edgar Wright’s action expertise is evident, the film stops short of greatness. Yet, it never descends into generic action fare, thanks in large part to King’s inspired dystopian world—a foundation that earns the movie points for creativity and entertainment. Still, as is so often the case, the book offers a deeper, more rewarding experience.

Why the Book’s Ending Leaves a Greater Impact

Where the movie adaptation takes its most significant departure from the source material is in its final act, which has divided both longtime fans and new viewers. Wright’s version opts for a comparatively hopeful conclusion: Ben Richards survives a dangerous plane crash, becomes a symbol for an emerging rebellion, and the epilogue suggests he lives on as a leader. While this could reflect a desire for a more optimistic narrative in today’s turbulent world, it strays from King’s original, more brutal resolution.

In the novel, Ben Richards sacrifices himself by crashing into the Games Network Headquarters, delivering vengeance at great personal cost. This act is final—Richards dies, ensuring that his rebellion comes at the steepest price. The rawness of King’s ending underscores the story’s central themes of resistance and the cost of justice. The movie, by contrast, offers a “too good to be true” coda where Richards survives, reminiscent of more uplifted tales like The Hunger Games or Batman’s Dark Knight Rises.

The shift strips away much of the anger and intensity that makes Stephen King’s story enduringly powerful. Richards wasn’t crafted to be a victorious Mockingjay or superhero but an ordinary individual angry enough to take on impossible odds. By allowing him a triumphant, almost mythic survival, the film misses the mark set by the book’s harsh honesty. Instead, it becomes easier to see the movie’s ending as a “dream sequence”—a narrative device giving hope rather than truth.

That’s not to say Wright’s adaptation isn’t enjoyable or worth watching. The cast, including Glen Powell, Josh Brolin, and Lee Pace, provide memorable performances, and the action delivers thrills. Still, many viewers—especially those familiar with King’s work—may find themselves wishing for the devastating punch of the book’s finale. If there’s one lesson to carry from either version, it’s the enduring value of anger channeled into purposeful resistance.

Meet the Key Characters in The Running Man

The character of Ben Richards remains central to both paperback and film, depicted as a reluctant hero drawn into conflict by extreme circumstance. Glen Powell brings this role to life in Edgar Wright’s version, capturing Richards’s struggle between personal yearning and public obligation.

Josh Brolin portrays Dan Killian, the manipulative architect of the Games Network, whose menacing presence underscores the dystopian threats Richards faces. Colman Domingo’s Bobby T provides a memorable supporting role, while Michael Cera, Katy O’Brian, Martin Herlihy, and Lee Pace each contribute, fleshing out a world of contestants, adversaries, and unexpected allies.

These performances, especially when combined with the film’s dynamic direction and soundtrack, keep The Running Man engaging. Yet, it’s Stephen King’s writing—the stark world, moral ambiguity, and emotional impact—that gives the story its lasting power.

Why Stephen King’s The Running Man Resonates Decades Later

The debate about which version of The Running Man is superior continues, but Stephen King’s novel stands out for its unflinching approach to dystopia and its dramatically potent ending. The book’s readiness to confront injustice without flinching ensures it remains relevant, especially in a world still grappling with themes of control, resistance, and personal sacrifice.

While Edgar Wright’s cinematic take offers entertainment and strong performances, it ultimately softens the story’s hardest edges. For readers seeking a more profound experience, or for those wishing to understand the original vision of Stephen King The Running Man, the novel remains the definitive version—one whose message stays with audiences long after the final page.