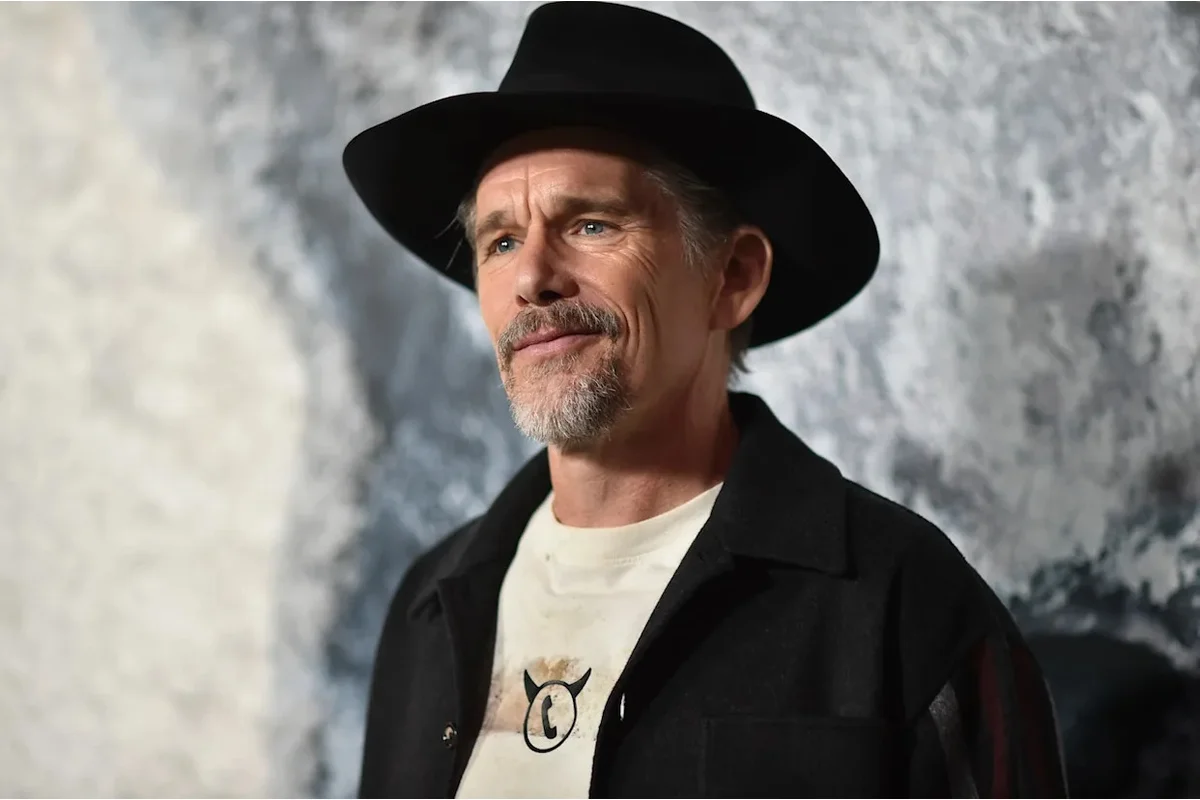

In a highly anticipated return, Ethan Hawke and Richard Linklater reunite for their ninth project, “Blue Moon,” exploring complex themes of partnership and professional dissolution. The film opens a new page in their collaboration, with Hawke taking the lead in a narrative set on a historic Broadway night in New York, further showcasing the enduring synergy that has defined their past successes like the “Before” trilogy and “Boyhood.” The focus keyword, Ethan Hawke Blue Moon, is central as Hawke delivers one of his most emotionally nuanced performances to date under Linklater’s direction.

Longtime admirers of Linklater and Hawke have come to expect a unique conversational dynamic from their films, and “Blue Moon” delivers with dialogue that balances philosophical musing and humor. Richard Linklater, known for keeping a low profile onscreen, is just as lively off set, engaging in rapid-fire exchanges with Hawke that mirror the energy at the heart of their partnership. Their bond, strengthened over three decades of collaboration, remains a vital component of their creative output.

Exploring the Unsung Story of Lorenz Hart

“Blue Moon,” based on Robert Kaplow’s script, gives Ethan Hawke the challenging role of Lorenz Hart, the acclaimed lyricist from the Rodgers and Hart duo. Hawke’s portrayal unfolds in the storied Sardi’s restaurant on March 31, 1943—the night “Oklahoma!” premiered on Broadway. For Hart, this evening evokes deep personal anguish, witnessing Richard Rodgers, played by Andrew Scott, and Oscar Hammerstein II, enacted by Simon Delaney, celebrate a triumph while Hart grapples with being replaced both professionally and emotionally. Set against this backdrop, the film draws attention to timeless standards such as “Blue Moon,” “Manhattan,” and “My Funny Valentine,” which bear the indelible mark of Hart’s lyricism.

Hawke’s performance as Hart is marked by a wit-laden delivery that conceals layers of heartbreak and self-reflection. The real Lorenz Hart, whose personal struggles with sexuality and longing are skillfully woven into the film, is depicted as witty and magnetic, yet shrouded by sorrow. This characterization is supported by period anecdotes and observations from figures like Mabel Mercer who called him,

“the saddest man I ever knew”

— Mabel Mercer, Singer. This duality of exuberance and sadness is central to the film’s emotional weight and its portrayal of Hart’s short, tumultuous life.

The Challenges of Casting and Character

The project was a decade in the making, with Linklater intentionally delaying “Blue Moon” until Hawke could bring the needed maturity to the role of Hart. The director and actor discuss how certain stories demand an artist who is at the right stage of life, recognizing that lived experience adds authentic depth to the performance. Linklater reflects on how age influences creative choices and the way films such as “Slacker” or “Hit Man” are shaped by the artist’s internal landscape, pointing out,

“Hart is an old 47 [laughs]. He dies at 48. There have been a few lives that were lived there already.”

Hawke, in discussing his own reflections on age in artistry, cites seeing Meryl Streep and Kevin Kline perform “Romeo and Juliet” as a testament to the value of maturity in storytelling. He recalls how their age brought intellectual depth to the roles, a nuance a younger actor might not possess. This observation underscores the film’s belief that stories centered on loss, regret, and creative yearning benefit from performers who have personally encountered life’s complexities.

Layered Humanity Behind the Witticisms

“Blue Moon” walks a fine line between humor and pain, with richly textured dialogue that amplifies each character’s internal conflict. Linklater and Hawke clarify that while Hart might appear as “the saddest man alive,” he was also celebrated for his charisma and vivacity—a fact Linklater supports by noting that,

“People loved Larry Hart. You don’t hear bad things about him…He was sitting on this bedrock of forlorn sadness. His sexuality was against the law. He was such an unusual physical specimen. We came to the conclusion that he never had the adult relationship that he dreamed of. It was never his to have—a loving, supportive relationship. He didn’t have that, and yet he wrote about it. It’s tragic. But he’s so witty, so smart, so biting. That’s what gives those songs their heft forever. Even if you’ve had the best life, you remember the ones that got away. You remember the rejections and the sadness. Those stay with you emotionally.”

“Even if you’ve had the best life, you remember the ones that got away. You remember the rejections and the sadness. Those stay with you emotionally”

— Richard Linklater, Director

This tension between outward glamour and inner sorrow is at the heart of Hawke’s portrayal, allowing audiences to see both the sharp, public persona and the vulnerable individual beneath.

Musicality and Quick-Witted Dialogue

For Linklater and Hawke, capturing the verbal dynamism of Lorenz Hart meant infusing the film’s dialogue with a rhythm reminiscent of a classic Rodgers and Hart song. This called for a pace and unpredictability that set the project apart from conventional scripts. Hawke discusses the challenge:

“It’s easy for Larry Hart to talk for 10 minutes straight. 10 minutes go by like that to him [clicks fingers]. That’s how fast his mind is working. That was the challenge for me.”

The director credits Hawke’s “quick neural firing” as a reason for his casting, emphasizing that not every actor could believably embody someone as intellectually agile as Hart. Hawke’s preparation focused on ‘erasing’ his own persona to reach the essence of Hart—a man defined almost entirely by words and intellect rather than physical presence.

Omnivorous Curiosity in Art and Life

The film grapples with broader questions about the artistic temperament, exploring whether creative individuals naturally adopt a voracious curiosity and multiplicity of perspectives. Linklater suggests that artists, including Hart, must maintain an “omni-voracious” appetite for experience, not restricted by conventional boundaries. Hawke observes that Linklater’s work often escapes the limitations of a single gaze—male or female—and instead strives for perspective-taking that captures the richness of human experience.

These discussions echo in their previous projects, such as the “Before” trilogy, which is noted for its gender-neutral sensitivity and willingness to examine events from multiple viewpoints.

“To know the world, you have to have experienced it,”

notes Linklater, highlighting how Hart’s longing and exclusion filled his work with genuine pathos.

Contained Spaces, Expansive Emotions

Much of “Blue Moon” unfolds within the confines of Sardi’s restaurant, and the decision to set the film in a single location recalls earlier Linklater-Hawke endeavors. The pair reflect on how their experience with tightly focused settings, such as the film “Tape” and the extended confrontation in “Before Midnight,” provided a blueprint for generating dramatic tension in enclosed spaces. Linklater points out that scenes might look like fights on the surface, but at their core, they are about reconciliation and connection.

Hawke elaborates:

“The movie’s about all these hearts breaking, but nobody wants them to break. Nobody’s there to be mean. They’re there to make things better. The inertia of their own energy, creates this friction.”

The tightly scripted environment intensifies the stakes, mirroring Hart and Rodgers’ attempts to process both their professional and personal separation.

“Like all breakups, it’s probably been slow. They say it sometimes takes 10 years to get divorced [laughs]. This has probably been 10 years in the making”

— Richard Linklater, Director

This slow unraveling of a partnership is rendered with both humor and intense emotion, deepening the audience’s understanding of the characters’ motivations and history.

Interpersonal Rejection and Growth

Another thread explored in the film concerns Hart’s unrequited affection for Elizabeth Weiland, played by Margaret Qualley. Hart’s rejection, according to Hawke, becomes a coping mechanism that distracts from the more profound pain of his separation from Rodgers. The film delves into the authenticity of rejection, how characters confront it, and how these moments inform their growth and self-awareness.

“There was something about it that just feels deeply human and strange to me,”

Hawke observes, emphasizing the resonance of heartbreak as a universal experience.

Linklater draws attention to the unique interplay between Hart and the young Elizabeth, highlighting the importance of listening and space in relationships. The largest transformation for Hart occurs not when he is speaking, but when he is finally compelled to listen—a pivotal scene that tests both the actor’s and the character’s vulnerability.

Professional Rivalry and Mutual Admiration

“Blue Moon” doesn’t shy away from examining professional jealousy, particularly in the entertainment industry. Both artist and director reflect on how time and shared struggles have turned youthful competition into mutual respect. Linklater dismisses envy, stating that,

“Artists shouldn’t be possessive. You don’t own anything…I always say that until Ethan falls off the wagon, we have this going. But, no, artists work so hard. They’ve all sacrificed a lot to get where they are. There’s a mutual respect. It’s like what Larry says – it’s kind of in jest, because you know he might not feel it. He says, ‘Your success is everybody’s success.’”

Hawke acknowledges the pain underlying this sentiment, but also its truth. The pair reference their circle of contemporaries—including Jack Black, Glen Powell, Billy Crudup, Sam Rockwell, and others—recounting stories of early rivalries that have since transformed into deep camaraderie. For those who endure the trials of the industry, longevity itself becomes something to celebrate, as mutual support fosters a sense of shared achievement.

Upcoming Projects and Creative Continuity

Looking beyond “Blue Moon,” Linklater reveals that another collaboration may be on the horizon: a 19th-century film examining the “hippies of the 1830s,” possibly featuring Hawke alongside Oscar Isaac and Natalie Portman. Still in the financing phase, the project is envisioned as a family of ancestors to their previous film characters. The director describes it as

“the ancestors to a lot, actually.”

Linklater and Hawke also entertain the idea of turning their creative process itself into a subject, with talk of making a film about the making of “Before Midnight.” The meta approach, full of self-referential humor and candor, perfectly encapsulates the playful yet serious tone that has made their partnership so enduring. Hawke remarks,

“We should do the making of the fourth – a fictional movie, the one that doesn’t exist.”

Asked whether they would consider a horror film together, Linklater jokes that filming “Before Midnight” was horror enough, remarking,

“That’s the movie we’re talking about. The making of Before Midnight! That is a horror film. Just no vampires.”

Release and Anticipation

“Blue Moon,” the latest collaboration between Ethan Hawke and Richard Linklater, is scheduled to premiere in UK cinemas on November 28. The film, deeply rooted in historical context and interpersonal drama, is expected to resonate with those familiar with the duo’s past works as well as new audiences seeking emotionally layered storytelling.

As the partnership between Hawke and Linklater continues to evolve, with projects on the horizon and reflections on their shared history, “Blue Moon” stands out as a testament to the power of artistic collaboration. Drawing on real-life personalities like Lorenz Hart, the project underscores how creative bonds can weather time and change, ultimately contributing enduring work to the canon of modern cinema.